Thanks to Patrons, $55 generated by this article went to World Wildlife Fund on October 1, 2021. Become a Patron here.

Located in Mason, Robert Clay Vineyards is an estate winery owned by Dan and Jeanie McLaughlin. The property is 50 acres. The vineyard is 20 acres. There are 15,000 vines, grown in rows anywhere from 300-750 feet long, divided into five blocks: Touriga, Merlot, Viognier, Chardonnay/Barbera, and Experimental. The Touriga grape becomes Touriga wine. The Merlot grape becomes Merlot. Etcetera.

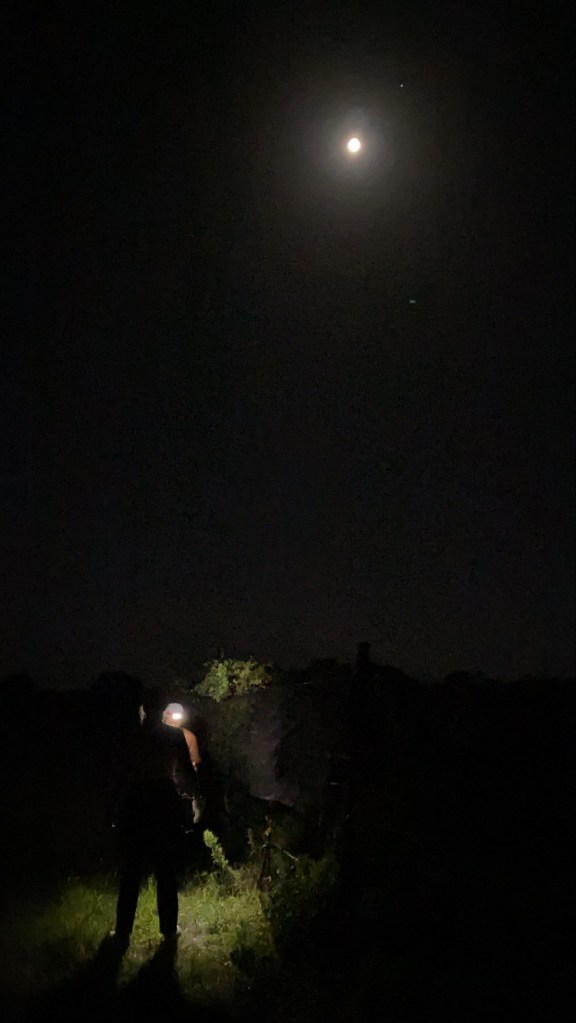

The five blocks of grapes encircle a clearing which includes a barn, some tractors, an RTV, trucks, geese, chickens, four dogs, a cat, and three trailers. Dan and Jeanie live in the first trailer; their son, Blake, 20, lives in the second. Dan is tall and careful and can at first appear serious, but then turns out to be the kind of guy who pulls stuff like, it’ll be 2am in the middle of a harvest, and Dan will lean in through a hole in the vines and hold a grape up in front of his headlamp and squish it in slow-motion and whisper, with a sly smile, “Dr. Pimple Popper.”

Jeanie is bright and fierce and comes across like an Olympic gymnast. Blake has a laugh which makes one question whether anything sad has ever really happened to anyone. He’s majoring in Oenology, the science of wine, which consists largely of chemistry and English classes, the English being for lab reports.

The third trailer, for helpers, is where I lived with Tim (Pennsylvania), Sarah (Kentucky), and Nadelle (Texas). All you need to know about our trailer is that there was this knobbly two-foot stick propped up in the corner of the bathroom. This stick had a name. It was named “the poo stick.” It was so named because sometimes, out of necessity, the stick had to touch some poo in order to support the trailer flushing mechanism. At least, this is what I was told upon arrival. It was hard for me to imagine poo in the trailer behaving this way because, due to the insane work hours of harvest, no one ever seemed to eat more than 200 calories at once. In my mind, there was nothing in the body to make the poo to begin with, much less make the poo substantial enough to require the poo stick.

I suppose another thing you might need to know about our trailer, to get off the subject of poo, is that to use the stove one had to turn on the gas, ignite a lighter, and stick the lighter into the gas until it exploded into flame, right around one’s fingers. In other words, every time I wanted to cook something, I was forced to undergo a minor cardiac arrest.

Robert Clay Vineyards is special in two ways:

1) In the wine industry, there are winegrowers, who grow grapes. There are winemakers, who buy grapes to make into wine. There are folks who do a combination of both. Then there are fakers, who sell bottles and do tastings and maybe grow some grapes for you to put up on your Instagram, but import their wines from other places. (Fun fact: a “shiner” is an unmarked bottle of wine, which a winery can purchase and accessorize with their own label. Shiners can be used in a sketchy manner, or they can be used when a winery is just beginning, and needs to wait a year or few for its first batch of wines to age.) Then there’s estate. Estate is full-pipeline, sans fakery. Robert Clay Vineyards is an estate winery. That means there’s a Robert Clay fingerprint on every grape in every wine—Dan and Jeanie put the grape through from vineyard to lab to winery to barrel to glass. Then you put it into your witless and ungrateful mouth.

2) Check the label on the bottle in your kitchen. It probably says “Contains sulfites.” Most wineries put in all sorts of chemicals and non-native yeasts to ease the process of winemaking (chemistry comes later in this post). Many wineries machine-harvest their grapes, which means whatever’s on the vine will end up in your wine. Do you buy cheap wine? You may be drinking a fermented cat. But that’s okay. I myself have probably inadvertently consumed five or six fermented cats in this manner. And I am allergic to cats. So. Anyway, Dan and Jeanie hand-pick their grapes, and take extra pains to avoid the chemicals that most other wineries use. They also try not to filter the wine, and instead let sediments naturally settle over the course of aging. These are called natural winemaking techniques. If you try their wine, you’ll find that the taste has the clean quality of a tiny silver spoon getting clinked against a tiny crystal glass.

I arrived at Robert Clay Vineyards on August 15. Two days before, Dan had been awake for 37 consecutive hours, working. Then he got three hours of sleep. When I arrived, he and Blake had been awake for 18 consecutive hours, working. We went out and harvested 830 pounds of grapes, and then took them into the winery and processed them. By the time we were finished, Dan and Blake had been awake for 24 consecutive hours. Was that normal here? For harvest, yes. With grapes, one is on Nature’s schedule. Which is a euphemism for: One has no free will and is chained to Nature by one’s neck whilst Nature races along the track of time, not even really along the track, Nature having forgotten to take its daily Adderall for its raging ADHD.

I came to Robert Clay Vineyards to help with harvest. Before I tell you any more about wine, let me tell you about harvest.

Harvesting (Winegrowing)

Harvest is approx. July 15 to August 28.

First, you harvest, or pick, the grapes.

There are two ways to go about it. There’s a day harvest, which goes from ~3am to ~11am, give or take a few. Then there’s a night harvest, which goes from ~7pm to ~3am, give or take a few. If you can’t be on your feet for eight hours straight, you can just give up and go home and drink a fermented cat.

How long a harvest takes depends on how many people are picking (we were normally a team of six), how densely graped the vines are, and how clean the grapes need to be. For instance:

- Our first Ruby Cab picking took 8 hours for two ~300-foot rows, because we brought foldable chairs and sat down and probed through each cluster one grape at a time. These grapes needed to be perfect in order to start a solid initial fermentation. Don’t worry if you don’t know what that means. We’ll go over the chemistry later.

- Our second Ruby Cab harvest took 9 hours for five ~500-foot rows, because we whizzed through them, only doing cursory checks. We would mix in the already strong native yeasts from the earlier batch’s solid initial fermentation, so we didn’t have to worry about perfect grapes.

- Fun fact: Ruby Cabernet is a designer wine made in 1936 at UC Davis. The juice is so rich and dark that it’s used to make the additive Mega Purple. All grapes come from the Noble Grapes. The way grapes grow, from one cluster, you can get seeds for twenty-five different grapes, because all the eggs are different. So from a cluster of Merlot (red) seeds, you can even get a white. This is something I do not understand myself and copied/pasted here directly from my notes, and do not plan on explaining further due to having already finished my coffee and still having to get out the rest of this damned write-up. All I know is that this is the reason vineyards are planted with cuttings, not seeds. If curious, ask Dan, who knew nothing about grapes before purchasing the property in 2012 and now, via books and Google, knows everything.

Day harvest (~3am-~11am): Alarm goes off at 2:30am. Risk death climbing off ladderless bunk in dark. Brush teeth, pump calories and caffeine, put on headlamp. Go outside. The first breath of cool (in Central Texas, ~77 degrees) night air fills you up and gives you the sensation of being lighter than you actually are. Ride this breeze to patio. Attain 6-inch sickle, red bucket (or yellow bin), and strap for hanging bucket from shoulder. Hear running and look up to see Flynn and Cleo, two sweet goofy Great Pyrenees, approaching at a fairly terrifying speed, smelling like they just ate a skunk/racoon/rabbit. Which is good. Keeping the vineyard free of skunk/racoon/rabbit is the job of the Great Pyrenees. These are working dogs. You are a working human. Tramp along with dogs to grape of interest; Merlot, maybe, or Cabernet Sauvignon (“Cab Sauv”), Touriga; Ruby Cabernet (“Ruby Cab”). Tramp up and down rows, pulling down bird nets wrapped around vines.

Return to initial row. Grab initial cluster of grapes. Break stem on cluster via violent jerk of sickle. Sleepy? Worry not. The violence is within you. Thumb off grapes with rot or birdpeck. Drop cluster into bucket. Move to next cluster. Repeat.

Soon, the half of your body which is carrying the bucket strap begins to sour. Swing bucket around to other hip in order to switch strap to other shoulder. Continue. Overhead, moon is white and bright with an outline so sharp it cuts your eyes. You can see the Milky Way. Actually, no. You can’t. You are supposed to be seeing grapes. So, go back to seeing grapes. Cut. Drop. Cut. Drop. Cut. Cut. Drop. Someone is playing music. Crickets are making own music. There is another thing making its own music and that is your left ear ringing because five minutes ago you felt a mosquito on your neck and threw your head back to crush it, only it turned out to be a red wasp and it stung you. Felt like a flu shot. Third music, therefore, is music of sleep-deprived brain tripping balls on red-wasp venom.

One hour down, seven to go.

Headlamp produces white light which illuminates 10 feet, max. Everything beyond is pitch black. It’s like light is sprinting and then smacks into a wall and dies. Think about it like this. If more than 10 feet into a row of grapes, look both ways and only see grapes, grapes, grapes until the end of the world where there is only pitch-black darkness with the assumption of more grapes. No way to predict how much finished nor how much to go. Only way forward is to think about cluster in hand and nothing more. Great life lesson to be learned from that.

Meanwhile, every gnat and moth within said 10-foot radius believes your head/headlamp combo is the moon. For that reason, once in a while, a gnat will try to land on your eyeball. Do not let this happen. It is very bad for morale.

From near distance comes shrill, demonic wail of a laugh. Then a bunch more. Sounds like six or seven small demons getting exorcised of bigger demons. Seems to be occurring just a few rows away. Prepare for possession. It’s 4am and you are weak. The power of Christ cannot compel you. Then find out from Dan that this is the sound of coyotes celebrating a kill.

Two hours down, six to go.

To keep functional, once every thirty minutes or so, bite single grape off cluster. Crush slowly between tongue and roof of mouth until pop. Cool sweet juice floods mouth. Placebo-effect sugar rush floods brain. Move forward with renewed vigor.

Pick and walk and pick and walk and pick and walk. And here is how it happens. You never actually see the sun coming up. But then one time you look up from the grapes and notice that the black sky has a soft line of pink and orange unfolding from the horizon. Pick and walk and pick and walk. The next time you look up, you see that the sun is suddenly already sitting fat and happy several inches above the horizon.

Once the sun’s out, there’s the additional factor of trying to maneuver the body into whatever odd formation it takes to avoid the UV and still wield the sickle without amputating a finger.

By the end of the final row, your hands are so sticky from grape juice they make little schmuck schmuck noises when you tap your fingers together. Your clothes are sticky with grape juice and drying stiff in the hot sun. Carry all the buckets you filled, which are heavy as rocks, to the big white bin on the tractor, which Dan or Blake drives over to the patio to load into the truck. Wash your hands, grab a protein bar.

Get inside the truck to ride to the winery for processing for the next 8 hours.

Night harvest (~7pm-~3am): Starting off, temperature’s still high eighties. Backs of legs are rivers of sweat. Insects are awake and active. To walk up a row is to be swarmed by flies, grasshoppers, black wasps, red wasps, bees, and mosquitoes, kamikazing in hordes off vines at the movement of your footsteps. Grasshoppers massive. Grasshoppers also dumb. Grasshoppers jump without knowing where they’re going and occasionally end up on your body. When they jump off again it feels like getting punched by a tiny person. Metaphorically speaking, grasshoppers in a vineyard is like getting punched by God. Grasshoppers will devastate an organic farmer’s crop.

Check for wasps and black widows, then duck head under vines to get a waft of what feels exactly like air conditioning. This is AC au natural. It’s the breeze blowing the water vapor in the leaves downward, and it’s how the grapes stay cool.

Forty minutes into harvest: a stab in Achilles heel. Feels like thorn with electrical current. Maybe a sticker (spiky bud of weed). Look down to extract sticker. Instead find dozens of coked-up fire ants enjoying what looks like multiple raves atop sneakers and ankles. Six or seven are anchored firmly into your flesh via pincer. Swipe them off in panic whilst acting blasé to maintain reputation.

Fifteen minutes later it happens again. In two days, make sure to avoid looking at ankles, which will be blistered by then. It may cause you to vomit. One ought to avoid vomiting in a trailer toilet. In a vomit situation one is out of the poo stick’s hands.

Other than the differences in insect warfare, night harvest proceeds about the same as day harvest.

When finished at 3:30am, load grapes into truck, stagger to trailer, set alarm, and have Kafka-esque nightmares of infinite loop of waking up to go to the winery for processing until alarm goes off for real at 7:30am.

Get inside the truck to ride to the winery for processing for the next 8 hours.

How does a winegrower know when the grapes are ready to harvest? About 3 weeks before harvest is expected, growers start conducting periodic random samplings in order to get a trend analysis. I participated in one during a light drizzle. We tromped up the rows and grabbed a random grape every ten paces, then mashed them up in Ziploc bags and took them to the lab. We tested for brix (sugar level) and pH, which you’ll find later are the holy grails of Dan’s winemaking. One thing we were looking at: the longer the grape stays on the vine, the more basic (higher pH, less acidic) it is. That’s not what we want. Not only does it make fermentation dodgy, but also, acidity in a wine means texture—whole milk vs. skim milk.

Why pick the grapes at such odd hours? Because these hours are when the sugar levels are most stable, making fermentation easier to control. Which brings me to…

Processing (Winemaking)

The drive from the vineyard to the winery is fifteen minutes of delirium.

1) Weighing: Via forklift, Dan or Blake shuttles the bin of fresh grapes to the weighing station. A full bin of grapes is generally ~1,000 pounds, with some variation due to the weight of each type’s fruit and stems. Barbera grapes, for instance, are thicc. Cab Sauv, less so. In the image on the left you see two full bins of Ruby Cab grapes, about to be delivered to La Cruz de Comal Wines after weighing. La Cruz de Comal Wines is an example of a winery which buys fruit from other growers, while also growing its own grapes.

2) Destemming + crushing: Via forklift, Dan or Blake shuttles the grapes into the winery. The two of them shovel them into a destemming machine, which separates the stems (called “rakuses”) from the fruit. The destemming process also crushes a lot of juice out of the grapes. For small batches, they might choose to further crush by foot-stomping, which must be executed carefully to avoid splitting seeds or getting too much oxygen into the juice. Dan or Blake may also choose to put the grapes through a pressing machine, which extracts every possible drop of juice, even from the skins. It all depends on the final effect they wish to achieve for the wine.

A nice destemming machine costs $60,000. As a result, Robert Clay Vineyards has a sh*t destemming machine. It often misses loose stems, or even full clusters. My role in the operation was to lean over the edge of the bin and pick these out of the “must”, or fresh grape juice still containing skins and seeds. Not all winemakers find it important to get the stems out. But stems increase pH (higher pH = more basic = less acidic), and Dan prefers for his pH to stay low, to avoid any possibility of the juice turning into vinegar instead of wine.

3) Sampling: There are two schools of winemaking. There are what Dan terms the “hippie winemakers”: those who deny there’s any science in the craft. Then there are those I term the “Dan winemakers”: those who see the whole process as chemistry grad school.

The following image depicts Dan collecting juice from the must.

Dan then takes the juice next door to the lab.

First, he measures brix. This is the sugar level. The sugar level determines the potential alcohol content of the juice—the more sugar you start with, the more alcohol you end with. Which leads us to, at last, fermentation.

FERMENTATION IS HOW THE JUICE BECOMES WINE. If fermentation is a story, yeast is the protagonist. See: title of this post, “yeastyboys” being coined by the crew about 75% through a 16-hour workday, at which point everyone was fairly dazed, and Dan was staring into a flask saying, in the tone of a chemistry professor, “If you look closely, you can see them waving their tiny hands and going, ‘Hey!’”

Yeast is a microscopic fungus consisting of single oval cells. Grapes have native yeasts, which are naturally present on the fruit. Most winemakers choose to add non-native yeasts to assist fermentation, which Dan considers to be some kind of cardinal sin. Yeast converts sugar into CO2 and ethanol (alcohol). It is not unlike you converting a burger into poo. Actually, it is very unlike that. But if you are not chemically oriented, you can think of yeast as eating sugar and pooping it out as CO2 and ethanol.

The juice goes into cylindrical bins or glass jugs to ferment. At the opening is the following device with fluid inside. During fermentation, the fluid bubbles maniacally. The bubbling is the CO2 being pooped by the yeast. It is a signifier that ethanol is being pooped by the yeast too. AKA, your juice is turning into wine.

Yeastyboys are high-maintenance. If there’s too much sugar, for instance, they have to work harder to convert all of it, causing them to become “stressed.” Stressed yeasts make weird-tasting wine. If the grapes aren’t clean (remember how the first Ruby Cab harvest was painstaking because we had to quality-check every grape, in order to start a strong initial fermentation? solid initial fermentation means strong yeasts), the yeasts can get out-competed by bacteria. Out-competed yeasts make weird-tasting wine. Or the yeasts can get killed by too hot or too cold. Dead yeasts make weird-tasting wine.

Make one weird-tasting wine, and your reputation is KO.

Winemaking is a euphemism for “high-stakes nursing of a bunch of high-maintenance yeastyboys.”

After measuring brix, Dan spins out the juice in a centrifuge, filters it, and drips it into a mass spectrometer ($42K!). The spectrometer measures a variety of quantities, like tartic acid level, malic acid level, volatile acid level (this is what makes vinegar), and pH. If you’re in or around the lab at this time, you may want to find a place to hide. The magic range for pH is 3.55-3.65. What usually happens is the pH is higher than Dan wants it. Dan is good about taking things in stride but a pH out of the 3.55-3.65 range is pretty much depression. “The winemaker’s entire job is just to keep the juice from turning into vinegar,” is what Dan says. A high pH risks bacterial growth. It can also mean a wine that tastes too “green.” pH is another thing that other winemakers might not mind. But we are talking about “Dan winemaking,” here.

Earlier, I mentioned the “Contains sulfites” note on a wine label. During fermentation, yeast will produce natural sulfites to fend off competition from other microorganisms like bacteria, which causes spoilage. Sulfites also protect the wine from premature oxidation. Almost all wineries will add non-natural sulfites at some point. Dan does it when he has to, i.e. to save a batch of wine from spoiling. But he calls it cheating.

4) Fermentation: After sampling, the must is transferred to a jug or cylindrical container for the just-discussed fermentation process. In the early stages of fermentation, the grape skins rides the CO2 to the surface of the must. Someone has to come “punch down” the wine 1-3 times a day, breaking this surface and adding oxygen to the juice. Punching down is for red wines; for white wines, the juice is normally separated from the skins immediately, because tannins and color aren’t desired.

During fermentation, Dan and Blake will often go into the winery and check on the must by sniffing. If you are ever invited to sniff a fermenting wine, chill out. Do not sniff hard. If you sniff hard like I did, you will get a wasabi rush and embarrass yourself. At first it always smells like juice, and you think you are fine, and then you keep sniffing, and then all of a sudden you’re sniffing fingernail polish and reeling back and getting cross-eyed and needing a moment to regain your identity which has been lost via the sleep deprivation and also now the dose of grape wasabi acid.

You can also taste the must at any stage of fermentation. It tastes like grape soda with an ever-increasing premonition of alcohol.

Often, Dan will take a sample to the lab too, in which case, if the pH is looking dodgy, remember that there are plenty of hiding places in and around the winery.

6) Barrelling: You can tell fermentation is over when the CO2 stops bubbling. After fermentation, the must is officially, and taxably, wine. The wine is transferred into oak barrels (red wines) or steel barrels (white wines, rosés) to be aged over the next year(s). Oak vs. steel is not a rule. But typically one does not wish to be served a rosé with an oaky flavor.

“90% of winemaking is cleaning up.”: This is what Dan said to me the first time we went into the winery for processing. We proceeded to spend three hours cleaning equipment—not only hosing down and powerwashing, but also spraying and scrubbing with different combinations of chemicals that would thoroughly purify each cranny—one hour processing, and then two more hours cleaning equipment. Since winemaking is such a chemical process, a few bacteria in the wrong place can wreck dozens of gallons of wine in one go.

If you like wine but don’t like washing dishes, I do not recommend getting into the winemaking business.

The Feds: The other 90% of winemaking is data entry. I know 90% + 90% =/= 100%. I meant to type another 90% because that is what it feels like. First of all, since you are working on Nature’s schedule, there seems to be twice as many hours in a day. Secondly, outside of harvest, you are either cleaning equipment or entering data, to the point where, if you find yourself actually doing something wine-related, it feels like you’ve made a mistake.

Dan uses InnoVint, a cloud-based enterprise software made specifically for winemakers. He is required by the government to track every single event, from the initial weigh-in to the mixing of different wines; how much, from where, what time, which sequence. The data is used to run a single tax report at the end of the year. Robert Clay Vineyards is so small that, last year, the taxes came out to be $12. But the opportunity cost of the hundreds of hours of data entry came out to $1Ks. The government makes the hoops for large commercial wineries to jump, and forgets that there are small family-owned wineries struggling to get one leg up and over the hoop at a time. On top of that, the government has no idea what it is talking about. Wine is made and discussed in millileters but the feds ask for measurements in gallons.

Also: federal and state governments have different requirements for winemaking taxes. As a result, Dan and Jeanie have to keep track of two separate sets of data.

The feds can be considered the most painful part of the winemaking process.

The Reflection

Why a vineyard? Back in 2018, when I was onboarding as a waitress, I was given a booklet of the restaurant’s wines. Each wine came with a flavor profile: full-bodied, rich, fruity, spicy, delicate, zesty, so on, so forth. It made each sip seem practically orchestral. Like you could taste the overall flavor yet also pick out the details—listen to a phrase yet pick out the violins, violas, cellos, piano. It made wine seem like art.

Some wineries don’t mind the science. Other wineries are more like Robert Clay, where Dan’s in the lab with a vial of juice, frowning over the brix and pH. But science or not, I still see the art. The brix and pH are only instruments that allow the winemaker to craft with his/her work a wine with all the subtle, surprising, tasteful touches that a wine booklet will ultimately list in its description. Writer and artist Percival Everett once told me, “The way to enjoy art is to find a window and enter through there. You can’t try and take it in all at once.” Since my time at Robert Clay Vineyards, I have been entering a sip of wine through the taste of the grape. Even after all the fermentation and aging and bottling, I believe that the original grape can still be pinpointed, at the very heart of the flavor, and followed out into all the labors which ensued. (Unless you are drinking Franzia, in which case what ensued from the grape was a lot of chemicals in a short period of time, and then a cardboard box. See if you can taste the cat.)

“Natural wines are about the vintage,” says Jeanie. It’s about what happened that year: the weather, minerals in the soil, the time the grapes were picked, the people who processed them.

So, what’s the vintage of Robert Clay Vineyard?

Nine years ago, Dan and Jeanie purchased the property to pursue Dan’s dream of working outdoors. The vines were in bad shape. The couple, living near Austin at the time, had 0 prior experience in grapes, wines, or even farms. They weren’t even wine connoisseurs. Their first harvest brought in 3 tons of fruit—only 1/10 of the expected crop. So Dan and Jeanie moved their entire family out to the vineyard and proceeded to completely overhaul the vineyard by cutting back, by hand, every single vine across the planted 14 acres. Sometimes they were out working in temperatures over 100 degrees. Thorns. Fire ants. Bee stings, wasp stings. Scorpion stings. Racoons eating the crop. Grasshoppers. Not enough manpower to get all the fruit off the vines when it needed to get off. Not enough manpower to get the nets over the grapes before the birds came to peck them to rot. All this, and still working a 9-to-5 to pay the bills. You read about my experience over 2 weeks of harvest. Imagine being on Nature’s schedule for 365 days a year, at the price of having uprooted your whole family in vain from a comfortable life in the city.

Dan recalls of rebuilding the vineyard, “One day it was about a hundred outside and the sun was coming down like crazy and Jeanie and I were both so tired. Jeanie was driving the tractor and I was walking alongside it. At one point, I just fell to my knees,” he says. “It was like that. I didn’t think,” he says, “that we could do it anymore.” That was the crop that was harvested and processed in 2013—your 2013 vintage wine.

And so said William Faulkner: “The aim of every artist is to arrest motion, which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that a hundred years later, when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life.”

—

Follow Robert Clay Vineyards: Instagram / Facebook / Website

Beautiful place, beautiful people and excellent writing !!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading & leaving such a kind message! It was a good time but still nothing can top Bodhi… 😊

LikeLike

“clean quality of a tiny silver spoon getting clinked against a tiny crystal glass”

As you know, I’m more of a beer gal, but this description of wine is the best I’ve ever read.

LikeLike

Excellent explanation of winemaking!

LikeLike

i can’t write a comment on the 16 days at the Kulung Organic Tea Farm article 😦

LikeLike

Fixed.

LikeLike